Every year, after Spring break, I begin our final literacy unit of the year. The unit is titled, “Uncovering Hidden Information, Sharing it With Others.” The focus of this unit is to look at how our understanding of the world is shaped by the information that we are presented with in the world around us and then to think about how the information that we choose to share with others has an affect on how they see and understand the world. As readers, we look at how the information that we take in affects our understanding of the world and how we can choose to take in information in a different way in order to gain a more accurate and complete understanding. As writers, we then think about how we can choose to privilege the kinds of information that have historically been left out, or ignored, or silenced by other writers. By doing this, we can actually use writing in order to help others to gain a more accurate understanding of the world.

I love this unit because it gives us one final opportunity to widen our definition of what it means to read and what it means to write and also look at the incredible power that these processes hold. During the last weeks of the school year, this unit gives us one more chance to really dig into the ways that my students can go out into the world beyond our classroom and continue the work that we started together in order to work towards a better and more just world.

Much of this work depends on my students understanding that what they have been told in the past and the messages that they have been subjected to since they were first born, have had an impact on the way they understand, or more accurately, MISunderstand the world around them. In order for this unit to work, I have to first help my students to recognize that they DO misunderstand the world around them. I need them to see that they carry inaccurate messages about the world and the people living within it, even if they believe that they don’t. In other words, I need my fifth grade students to recognize their own biases so that they can work to confront and dismantle them. This is a task that is difficult for most adults to do and I need my fifth graders to do it.

I have written several posts in the past about the way that we do this work, but I wanted to take some time now to write about how we did this work this year. Much of what we did this year was similar to work I’ve done in the past but I like to take time each year to write about this work anyway because it allows me to look back and reflect and do better for the next year.

One of the things that I know to be true with kids (and with grown-up, too) is that I can tell them all sorts of things, but if I am not able to find a way to have them really see those things for themselves, then they are not meaningful and they will not truly impact the way they think and act in the future. Any time that I can help kids to discover a truth instead of telling them that truth myself, the learning that takes place is much more powerful. For that reason, I often look for ways to make abstract concepts more concrete and visible for my students. There is all sorts of research that supports this concept, but what matters most to me is that I can see the difference in the ways my own students respond to the learning.

So, in order to help kids to “see” their own biases, to see their own misconceptions about entire groups of people, I lead them through two different exercises before ever revealing to them that we are doing work with bias at all. I begin by telling my students that we are starting our final unit of the year which will focus on using clues in the world around us to make inferences and then also provided clues to others in order to help them to infer truths about the world. This is true. But not the whole truth. I do not yet tell them that the clues we are surrounded by in our current world often lead us to inaccurate inferences that are weighed down by bias, racism, sexism, etc. That will all come later.

Draw-A-Scientist (Plus More)

The first thing that I hand out is based on a well-known experiment often referred to as, “Draw A Scientist.” I first read about this experiment and the results over time in THIS ARTICLE from The Atlantic. It provides a nice description of the experiment and what the results often reveal about gender stereotypes in children. The idea behind this experiment is that children’s drawings can reveal truths about the images that they hold and the way that they see the world. So when kids are asked to draw a scientist, and the majority of children draw a man, we can start to understand the way children view a scientist and who is most likely to be a scientist. When I first read this article, I was fascinated and could not wait to try this with my own students. Since then, I have added to this idea in order to give us more data to look at together.

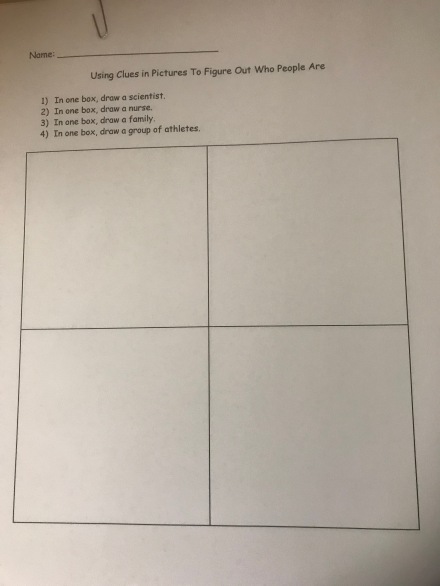

So on day one of our unit, I hand out THIS FORM to my students.

I tell them to draw these four images in whatever order they want and to make sure that they include detailed enough drawings in order for other people to guess which picture is showing which person or group of people. I tell them that we will be looking at these images later in order to guess which box contained which person or group of people. And then I don’t allow questions, I don’t provide any further explanation or direction, I just let them draw. When the drawings are complete, I then collect them and hold on to them until we are done with the next part of our work.

Here are a few samples from my students:

In my classroom, once I have collected these drawings, we move on to looking at picture book covers and matching them to summaries in order to reveal biases in a different way. I will explain that work later in this post, but I want to share the rest of this activity first. The reason that I stop after collecting the drawings is because at this point, most of my students still do not realize that we are doing work with bias. I find that as soon as they figure out what we are doing, they change the answers that they might give to the work with matching book covers with summaries and the activity is not as powerful. So, if you are planning to do both activities, I recommend stopping here, doing the picture book activity and then coming back to analyze the drawings. But, once you are ready to move on, here is the work that we did.

The next day, I handed my students drawings back to them. I asked them to use their drawings in order to respond to the questions on THIS GOOGLE FORM. The google form asks the kids to look at their drawings and record the genders that they used and the people that were included in their drawings. Once they have answered these questions, I have them close their computers and we look at the responses all together. What is great about collecting the data this way is that we end up talking about CLASS TRENDS and not the answers of individual students. What this allows us to do is to think about the messages that we collectively hold about groups of people in a way that does not single out any one student. I have found that this creates a safe space for students to be willing to wrestle with the ideas of bias in a much more honest way. The truth is that kids ALWAYS end up sharing brave truths that make them extremely vulnerable, but I know that those truths are difficult and cannot be forced out into the open.

So, I project the responses in graph form onto the whiteboard and I simply ask the kids to start to share what they notice. Here is a collection of what those results looked like this year in one of my classes. This year, I had a totally even split between male and female drawings for the scientist picture. So the kids were more interested in talking about the nurse drawings, which showed a majority of female drawings. I asked the kids to talk about why they think this might be. We started with comments about how there are simply more female nurses in the world. Kids shared that most often when they have nurses, they are female. And then, as always happens, there is one comment that pivots the whole conversation. This year, one student shared that she actually always has a male nurse when she goes to her regular doctor, but when she went to draw her picture, she actually drew a female. She said that she thinks that this is because on tv and in movies, nurses are always female. And this is all it took. Before I knew it, the comments kids were making started to dig a lot deeper into the idea of biases and stereotypes. That led some kids to start to focus on the data of the family drawings. Again, the kids talked about how they noticed that almost every picture drawn included one mom and one dad. Then, they began to talk about how even though they KNOW that not all families look the same and they would be able to tell you that, when they were asked to draw a family, they still all drew very similar looking families. At this point, the kids were really off on their conversations. They had so much thinking that I was worried we were going to lose some of it. So I stopped our whole class discussion for the day.

Matching Picture Book Covers to Summaries

The work that we did this year with matching picture books to summaries is similar to work that we have done and I have written about often in the past. So, feel free to look back at THIS BLOG POST or THIS BLOG POST to find out more about what we did. Here is a quick over view of how the work went this year.

After I collect the students’ drawings for the Draw A Scientist experiment, I have them grab their computers and meet me over in front of the whiteboard. I tell them that while in our first bit of work, they were creating the images that would help us to think about how we use clues to infer, in this activity, they would be using the clues in the images provided on the covers of picture books in order to help them think about how we infer what a book might be about.

I tell them that I am going to hold up two picture books. I have covered up everything but the images of the people on the front of the books. Then, I will provide them with two summaries and they will be asked to guess which summary goes with which picture book. I tell them that when we are done, we will look at how we guessed AS A CLASS and then talk about what clues helped us to make our guesses before I tell them which book goes with which summary. And with that we begin.

From there, the kids go to THIS GOOGLE FORM. I then proceed to hold us two books at a time. This is what the sets of books look like:

For those who are interested HERE IS A LIST OF THE TITLES AND AUTHORS OF THE BOOKS I USED AND THE SUMMARIES THAT GO ALONG WITH THEM.

As I hold us the two books, the kids make their guesses on the Google Form and then I move on to the next set. At this point, there is no discussion and the students answer on their own. When we get through all five sets of books, I ask the kids to close their computers.

And then, I project our results on the white board. HERE IS WHAT THE RESULTS LOOKED LIKE IN ONE OF MY CLASSES THIS YEAR.

We look at one set of books at a time and before I tell the kids which book matches which summary I ask them the following question, “Who would be willing to tell me what clues you used on the cover of these books in order to help you make your guess?” And the students begin to talk about how they made their guesses.

This year, the first two sets were guessed fairly accurately and so the discussion did not lead to any powerful insights. However, then we got to the third set of books. As a reminder, these were the books and these were the results:

So again, I asked my students who would be willing to share what clues they used to help them make their guesses. And here are some of the things that my mostly-white students shared: Students shared the girl on the book 6 cover looked lonely and seemed “different” and might have been made fun of like in “other books they’ve read.” They mentioned skin color and how they have often read books that show black children being treated unfairly because of skin color.

And then I told them that most of them had guessed incorrectly. When I told them that book 5 was actually about a girl who moves from Italy and speaks no English and is made fun of, they were really shocked. It led us to a conversation on why we might assume that a child with black skin was more likely to be considered, “different” and why we would assume the book would deal with the child being made fun of. We talked about books they’ve read in the past and how limited they are.

At this point, several students started to see what this work was really all about. So then we moved on to looking at our next set of books and our next set of data on the results:

With this set, kids spoke about how they immediately assumed book 7 took place in a country in Africa, that the people on the cover were poor and that it therefore dealt with sadness and struggle. Some students started to willingly admit they knew they were wrong. One student brought up our work earlier in the year with the idea of a “single story” and how many of us were probably making our guesses based on the single stories we carried.

Then, finally we look at our final set of books and data:

At this point, most kids realized that every single one of them answered this set incorrectly. Before I told them they were all wrong, they shared that they guessed book 10 was about a struggle for equal rights because the people on the cover were black. One child shared that he didn’t even see how happy they all looked when he first saw the cover. When I told them they were all wrong, we talked about how while, yes, the struggle for civil rights for Black Americans is a huge and important moment in history, not every book with black characters is about that struggle. And while Black people were engaged in that fight for civil rights, there were white people who were the ones benefitting from that unfair system and we do not often think about their role.

This is where we ended our conversation. The next day, we returned to the drawings that we had made in our Draw-A-Scientist (Plus More) experiment. As described above, I handed back at their drawings, I had them use the google form explained above to gather data on who they draw in each picture and then we looked at the results together and began our whole group discussion.

On day three, I knew that my kids had SO MUCH to say about our work so far and this year, I wanted to make sure to provide them time to really look at the data in small groups. One of the things that I have noticed in our whole class discussion is how much time is taken up by the same voices. To try to work on fixing this, I was much more deliberate about allowing time for individual reflection and small group thinking to help more voices to be heard.

So, on day three, I printed out ALL of the data from this experiment PLUS the results from the picture book cover experiment (which I will describe in a moment) and I asked the kids to first work on their own to look at the data that they found more interesting and then work in small groups in order to do some NOTICE/THINK/WONDER work. I asked them to USE THIS FORM in order to record some of the observations they noticed about the data, what those observations made them think and what those observations made them wonder. I modeled this for them and then sent them off to work. Here is what the modeling looked like:

Once they had a few minutes to work on their own, I had them gather in small groups and share what they had recorded and add to their thinking. Finally, I brought them all together to share what they had written down and to continue growing their thinking. As they spoke, I tried to gather some of the things they were wondering about on chart paper. They had amazing thinking to share, but I knew that the questions they were left with would be what guided the next step of our work, so that is what I tried to capture. Here are some of the things that they shared:

As always, I was amazed by the level of discussion that my students were willing to engage in. Unlike adults, my fifth grade students are willing to accept that they carry biases and that those biases lead them to inaccurate thinking and understandings about the world. When we frame these conversations around the idea that the world they are living in is sending them biased messages and racist messages and sexist messages, they are willing to look more closely at that world in order to understand where these ideas of coming from. They are eager to understand how this happens, so that they can stop it from happening. They want more control over their own thinking and so they are willing to engage in the necessary work even when that means they must confront their own thinking in a way that can be painful and difficult.

Doing this work with kids is so powerful because it gives me hope that we can help them to do better than we have done. Once they come to believe that they are carrying biases and stereotypes, they are so eager to learn how to fight against them. And that is the work that this world so desperately needs.

I’m sharing this with out fourth and fifth grade teams. Thank you for putting all of this work together in one place, for sharing with others. This is how we do better.

I’m so impressed with your approach and mission. Thank you on behalf of all of us.

This post requires sharing! What an example of “low floor/high ceiling” task to ensure all students access and engage in this critical discussion. I will be teaching 6th grade at a school with 95+% poverty and Home for our refugee students. I will look forward to engaging in this lesson with them.

As a former Math Specialist, we would ask kids to draw them doing math. We would receive art depicting a child at a desk or a teacher at a board 99% of the time. It was a powerful motivator for professional educators to rethink how they engage their students in mathematics.

I just wanted to thank you for this. I’m using it as inspiration to start conversations with my 10th graders. It’s amazing that your 5th graders are doing this work. Again, thank you for sharing all of your resources and ideas.

Even though I am from a different country, I think this unit will be a great one for my fifth graders because we all have biases.