One of my favorite parts of the end of the school year is watching as the students become the teachers. All year, I have modeled for my students how to read like writers and how to learn from the writers we love. And now, this is something that my students know how to do on their own. So it is time to let them show me.

Our final writing work of the year involves informational writing. Our first project was to create our own, student-written website that resembles the brilliance of the website Wonderopolis. As we did this work, my students had a chance to select their own mentor texts, analyze those mentor texts and then teach the writing strategies they discovered to their classmates. You can read about that work HERE.

For our next unit, we started to work on creating longer pieces of informational texts. As we began this work, each student selected his/her/their own mentor text. Here is an explanation of that process.

As the students got farther along in their research on the topics they chose to write about, I knew it was time to start thinking about how they were going to write. One of the biggest challenges that I have found with my 5th grade writers is helping them to do more than write a giant list of organized facts and instead write something that is interesting, clear and even evokes an emotional response from the reader.

The best way that I know how to help my students learn to write this way is for them to look to the incredible informational picture books that we have in our classroom and in our library. So as students started moving from researching into writing, I asked them to pull back out the mentor texts that they had selected. I asked them to especially pay attention to the mentor texts that they had selected for writing style.

I began by sharing my own mentor text, RAD American Women A-Z. I put a copy of a page from this text under the document camera and also gave a copy to each child. We read through the page together first without stopping. Then I told them I was going to go back and look for any parts of the writing that seemed like MORE than just a listing of facts. I was looking for places where the writer did something that helped make the information clearer to the reader or that helped make the writing more interesting or that helped the reader to feel some kind of emotion. I marked the writing strategies that I found and I asked the students to do the same thing.

Then, I told the kids that they were going to look more closely at their own mentor texts in order to find the writing strategies that their writers used. I shared with them that if they were no longer feeling inspired by the mentor texts they had chosen, then they should go choose new ones. Find something that moves you and then figure out how that writer did what he/she/they did. We discussed that while we cannot steal the words of other writers, we can indeed steal their strategies. That is how we become better writers.

So the kids headed off to analyze their mentor texts and to discover new writing strategies. They kept track of what they found HERE.

The next day, I pulled out another one of my mentor texts. I reminded them that on the first day of my work, with the mentor text RAD American Women A-Z, I saw my writer use stories to show something important about the topic. In my second mentor text, Incredible Inventions, I saw a totally different writer, using the same writing strategy to write about a totally different topic. I told my students that this was important because it helped me to see more than one way to use a writing strategy. I told them that as they looked at their own mentor texts today, I wanted them to see if they noticed two different writers using the same writing strategy. I asked them to mark this on their charts. And off they went again. This seemed to help them move from simply finding interesting content, to actually finding the strategies that writers were using to make the content more interesting.

On the third day, I told them that it was now time to select a writing strategy that they had seen used in their mentor texts to teach to their classmates. We had done this in our last unit, but I realized that when we did it the last time, I did not provide nearly enough support in helping them find effective ways to teach others about their writing strategies. So this time, I wanted each student to come up with a lesson plan.

I began by explaining to my students one possibility for a structure for an effective writing lesson. I used this chart to help explain the gradual release of responsibility model to them:

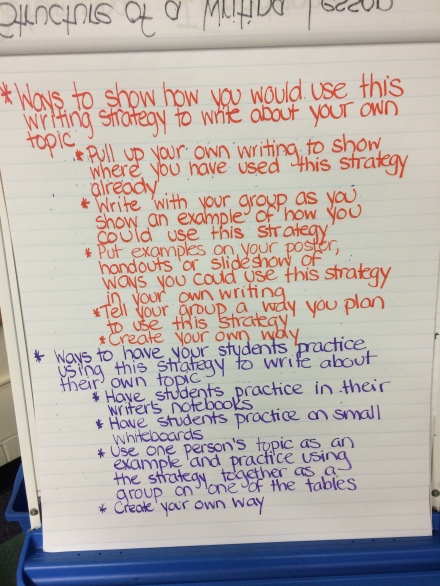

I also shared this chart with them in order to give them some ideas on how they could show how they might use a new writing strategy and to give them some ideas on how to have the students they would be teaching practice using this new writing strategy as well:

I then told the kids how teachers create lesson plans so that they know how they are going to teach their students. I told the kids that to help them to be better teachers, I was going to have each of them fill out a lesson plan as well. THIS IS THE LESSON PLAN EACH CHILD FILLED OUT. After creating a lesson plan, I asked each child to create something for their students to look at. Once this was made, I collected the visual aid and the lesson plan.

I did allow students to work together because I know that for some kids, leading a group of other students by themselves feels like too much. So the kids who worked together turned in one lesson plan and one visual aid. If the visual aid was a handout, I made copies for the students and if it was something on the computer, I just checked to make sure the teacher knew where to find it.

It was amazing to see what a difference the lesson planning sheet had made. The last time I had the students teach each other new writing strategies, it was a bit more of a free for all. Some of the kids did a great job and other kids just weren’t quite sure what to do. And that was my fault. Of course they don’t know how to plan a lesson. I also didn’t give them enough time to plan a lesson in the past. I just sort of threw them into the work. Having the structure of the lesson planning sheet gave the kids the direction they needed.

It took the kids about two days to plan their lessons. Some students needed more time to go back and find examples of writers using their strategies and other students needed more time to find ways to use these strategies themselves. While they were lesson planning, they were also using some of our writing workshop time to continue their research and drafting.

Today, they were ready to begin teaching. I created a sign up sheet so that we could keep track of who was teaching, what strategy was being taught and which students would be attending which lesson. Just like the last time we did this, I only allowed five students to sign up for each session because I didn’t want there to be one session that had 12 kids while another one only had 2. Here is what our sign-up chart looked like:

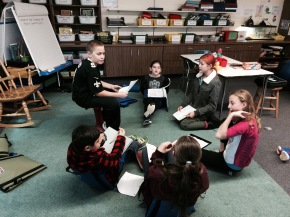

When I asked for volunteers to teach on the first day, almost every single hand went up. I ended up having to randomly select popsicle sticks with names because everyone was so eager to go first. The three teachers were chosen and went off to set up. I told the rest of the kids to think about the three writing strategies being taught that day and to think about their own topics. I told them that they should sign up for a strategy that would work for their own topic. This way, they could learn something that would actually help them in their writing.

Here was our chart after everyone signed up:

After signing up, the students went off to their groups with the things that they were told they would need. When they arrived in their groups, the first thing that they had to do was add the writing strategy to their build-your-own revision checklist. In our classroom, we often use revision checklists to help the students to be more independent in the revision process. For most writing units, I create the revision checklists by listing all of the writing strategies that we have learned in a unit and then asking the students to select a certain number of strategies that will work for their own writing in order to revise. But for this unit, the students would all be learning different writing strategies, so I created a build-your-own revision checklist. THE REVISION CHECKLIST TEMPLATE CAN BE SEEN HERE.

After the new strategies were listed on everyone’s revision checklists, the teachers in each group began teaching. It was incredible to listen to and incredible to watch. The language that we had used all year to talk about writing and to talk about the texts we were reading was now coming out of the mouths of these students who were assuming the role of teacher. I watched as kids redirected the students in their groups. I listened as kids asked the students in their groups probing questions. I heard students encourage each other and make writing suggestions to each other. It was clear that these kids felt ownership over the writing process and over this writing work.

Next week, the rest of the students will have a chance to teach their lessons. As students finish up their first drafts of their informational writing, they will move into the revision process with at least three new writing strategies to apply to their own writing, on top of the writing strategies that they have discovered on their own from their own mentor texts.

I think about how much quicker it would have been to choose four or five writing strategies myself and to teach them to all of the students at once on my own. Some kids might have even learned the strategies better if I had taught them.

But then I think about how much the kids would NOT have learned. They would not have learned that they can learn new writing strategies on their own. They would not have learned that some of the best writing teachers they will ever find are the books that they read. They would not have learned that they have the power to learn from and teach each other. They would not have learned what it feels like to know something well enough to teach it to someone else. They would not have learned that learning from each other is one of the best ways to solidify a community. They would not have learned that they do not need me to be writers.

And all of that is so much more important to me, and for them, than the efficiency that might have come from controlling all of the learning myself.