This year, I was inspired by other incredible educators to do a mock Caldecott unit with my students. I thought it would be just a fun thing to do with my students in those somewhat difficult weeks between Thanksgiving and winter break. It is often a time when both students and teachers can feel as if they are just waiting out the time until winter break begins. So I thought a mock Caldecott unit would be the perfect fun activity.

And that is really all I thought it would be. Fun. And then, once again, my students showed me how wrong I really was. Our mock Caldecott unit turned out to be so much more than fun. As we get ready to head back to school and vote for our mock Caldecott winner, it is amazing to me to look back on the work we have done and see how much learning took place during this unit.

I never would have done this unit if I did not have other incredible educators to learn from. There are so many amazing people who have done mock Caldecott units and have been incredibly generous with their material online. Everything that I have done and everything that I am happy to share, has been based off of the ideas of others. And for that I am incredibly grateful.

I began my unit the week we came back from our Thanksgiving break. As the students walked into our classroom, they were greeted by the ten picture books that I had chosen to be our potential mock Caldecott award winners. These were the ten books that my students would be working with very closely for the next few weeks.

What I learned about the Caldecott award, because I knew almost NOTHING about it before I began this project with my students, is that there is no predetermined list of books that can win the Caldecott award. So educators around the country simply guess which books might have a good chance of winning and use those books to run their own mock Caldecott units in their classrooms. After looking at the lists of many other educators, thinking about what books we have already used in my classroom, and simply falling in love with certain picture books that were published in 2015, I ended up with the following list of ten picture books to use in my mock Caldecott unit:

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt De La Peña (Author), Christian Robinson (Illustrator)

My Pen by Christopher Myers (Author, Illustrator)

Wolfie the Bunny by Ame Dyckman (Author), Zachariah OHora (Illustrator)

Lenny & Lucy by Philip C. Stead (Author), Erin E. Stead (Illustrator)

Float by Daniel Miyares (Author, Illustrator)

If You Plant a Seed by Kadir Nelson (Author, Illustrator)

Drum Dream Girl by Margarita Engle (Author), Rafael López (Illustrator)

Finding Winnie by Lindsay Mattick (Author), Sophie Blackall (Illustrator)

Yard Sale by Eve Bunting (Author), Lauren Castillo (Illustrator)

The Whisper by Pamela Zagarenski (Author, Illustrator)

What I know now is that the list itself doesn’t so much matter for this work. Yes, it would be incredible if the actual winner was a book that we had looked at and analyzed, but the real power of this project is that it can work with any picture book. And what I also found out throughout this unit is that some of the books that I so carefully chose, ended up not being big hits with a lot of my students. Nonetheless, this was the list we used.

On our first day of work, we simply learned about what the Caldecott award is, who has won in the past, what the requirements are for winning, and what the criteria is that the books are judged by. On the first day, I also shared an ENORMOUS stack of books that I had checked out from my school library that included as many past award winners and honor winners that I could find. My amazing librarians were so excited to help me with this work and enjoyed pulling out books that had won the award a long time ago that no one has looked at in years.

The rest of the kids time that first day was spent looking through these past award and honor winners and simply making observations on the illustrations. They were able to do this work alone or in groups and were asked to jot down simple notes on THIS form. From day one, I was amazed by the level of conversation that some of my students were having about the illustrations.

What struck me the most from the very first day of our mock Caldecott work is that students who had never before participated in our discussions about books were eagerly adding to these conversations. It quickly became clear to me that one of the best things about this work is that it was an “in” into the powerful reading community that we had built in our classroom for the students who had yet to find another way to enter. Students who had been reluctant to join this community or had not been able to figure out how to make themselves a part of it, were able to easily enter our reading community through the work that we were now doing. That continues to be THE most powerful aspect of this work.

After this introduction to the Caldecott, the next step for me was to introduce our ten potential winners to the kids. I shared with them each of the books that we would be using. We talked about the books that we had already read together as a class and then we spent the next few days simply enjoying the other books together. We read through the books simply to enjoy them and did not do any work analyzing the illustrations.

After becoming familiar with all of the books, I had to find a way to help my students to see the level of discussion that I hoped we would reach about the illustrations in our books. The problem is that I was not sure that I, myself, was capable of the kind of discussion that I wanted my students to have. I know very little about art. I don’t think that much about the illustrations in picture books in a critical way. I needed some help.

So I reached out to the absolutely brilliant art teacher at my school and I am so thankful that I did. After sharing with her the work that we were doing, we came up with a plan. When I want to make my own thinking visible to my students, I do a read aloud. I stop and model for my students the thinking that I am doing and then help them to do similar kinds of thinking on their own. Except here, I did not want my students to think like me. I wanted them to think like my art teacher. So SHE was going to do the read aloud. She very generously offered to do a few think alouds where she would talk about what she noticed in the illustrations. She every more generously, offered to let me video tape these think alouds so that I could share them with both of my classes (and with anyone else who might need them.)

So on the next day of our work, I shared THIS VIDEO with my students. They all sat in silence and awe as they listened to the way that Mrs. Hamm (our art teacher) talked about the way she looked at the illustrations. We then watched THIS SECOND VIDEO so that we could see how she looked at books in comparison to each other.

On the next day I introduced the child-friendly criteria that we would be using to evaluate the illustrations in our ten picture books. I shared with them OUR EVALUATION FORM that each student would eventually fill out for each of our ten books. And then, to help them better understand some of the artistic terms that we would be using, we watched THIS LAST VIDEO from our art teacher.

Once the students had this knowledge, we were ready to begin analyzing some illustrations. Before I had them work on their own, in small groups, I wanted to model together how we might fill out an evaluation form for a book. So shared the book The Night World by Mordicai Gerstein. While it was a book that I loved, it did not end up on our final list of ten. So it was a perfect book to use in order to model the kinds of thinking we might do about the illustrations in a book and how to turn those thoughts into notes and scores on our EVALUATION FORM.

One of the first important discussions to come up revolved around the importance of our evaluation criteria (which came directly from the actual Caldecott criteria, which can be found HERE). At first, many students were making comments about whether they liked the book or not and whether they liked the illustrations or not. So one of the first things we had to learn was to push past whether or not we LIKED a book and its illustrations. Instead, we had to look at how well each book met the listed criteria. In order to this, we had to get good at making a claim and the supporting it with specific examples. If we said that we thought that a book’s illustrations did an excellent job of making the story better, then we had to be ready to point to specific places in the book where this happened and provide an explanation of our thinking.

We also had the important discussion of how we could debate without arguing. That in a debate, we had to each be able to say our opinion, then listen to the opinions of others and then respond and then move on. In this way, we could stop ourselves from having the kinds of circular discussions that do not lead anywhere knew.

With these discussions came the realization of just how many important skills we would need to use and practice in order to do the work we needed to do. This was the day that we began listing together all of the goals that we had as we went through our mock Caldecott unit. The first one that we listed was to work towards debate versus argument. And the second goal we had was to support our claims with evidence.

After our whole-group practice, the next day we were ready to split into our small groups and begin evaluating our ten books. I split my classes into five groups, each with three or four students in the group. The groups would work together to evaluate all ten of the books. Each day, I handed each group two of our ten books. I paired the books based on length and tried to match shorter books with longer books.

On our first day of group work, I handed each student all ten of the evaluation forms that we would be using throughout the rest of the unit and asked them to put them into their reading binders. On that day we talked about the importance of starting out be either completely rereading the two books they were given, or at least flipping through the entire book to review the illustrations before filling out their evaluation forms.

And then I let the kids get to work. As I walked around the room on that first day, I heard some great discussions and really saw the kids analyzing the illustrations in the book and constantly referring back to the criteria. What I also noticed is that they weren’t doing as great of a job building on the ideas of the group members. It was almost as if they were each having their own conversations while sitting together in a group.

So the next day, before they got two new books, we had a mini-lesson in which we built charts to help us think about ways that we could build on the ideas of others. This became our third big goal. Here are the resulting anchor charts:

After creating our charts, the kids got back to work. Again, after having the discussion about how to build on the ideas of others, I noticed a significant improvement in the level of conversation that the kids were having. I even saw a few kids walk over to our anchor charts to help them remember the language that we had suggested using.

The next day, for our mini-lesson we checked back in with our charts and talked about the ways of building onto the ideas of others that the kids found most useful. We also talked about how we could push ourselves to try and use the ways of building onto the ideas of others that didn’t necessarily come as easily for us.

On our third day of evaluating I noticed that one area that the kids were still struggling with was listening to the viewpoints of others that did not agree with their own. So this became our goal for our last two days of evaluating. The next days mini-lesson was all about how hard it is to keep listening when you disagree with someone. But I asked them all to try to do it anyway. We talked about how many adults struggle with this and we all agreed that we could be better than most adults.

We added this last goal to our anchor chart of goals and here is the final product:

After five days of working in small groups, the kids had evaluated each of our ten books. In those five days, we had practiced supporting claims with specific evidence, practiced how to listen to each other, how to have discussions that led to new thinking, how to listen to people even when you don’t agree with them and how to allow our thinking to grow and change as we learn from the people around us.

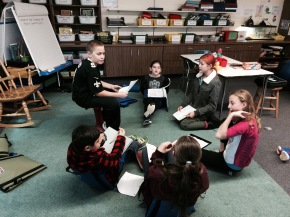

And the kids were so incredibly engaged. You could see it and feel it as you walked around the room. And though I don’t think a picture can capture the work that took place, here is a look at how well the kids were working:

After the kids had finished all of their evaluations, it was the second to last day before winter break. The kids were ready for vacation and there was that chaotic energy in the air that can really only be felt in a school building on the days leading up to winter break. And yet.

I asked the students to each take time to rank all ten of our books using THIS FORM. I asked them to look back at the notes they had taken, their evaluation forms and the books themselves. I asked them to take their time and really think carefully about where they were putting each book.

And they did.

It was silent. The kids put so much effort into creating a list of their top ten choices. And then they got into their groups and discussed their lists in an incredibly focused and powerful way. And many of them even made adjustments after talking with their groups.

It. Was. Incredible.

And so yes, we haven’t even voted yet. We will do that when we get back from winter break. We will come up with an award winner and with two honor winners. And then we will come together with classroom across the country in a Google Hangout where we will each reveal our award winners and honor winners.

I cannot say enough about how powerful this mock Caldecott unit has been. I cannot say enough how grateful I am to all of the teachers who helped me pull this off with my students.

The lessons that we learned through this unit are ones that will serve as the foundations for many other types of work that we will do in the second part of our school year. The lessons that we learned through this unit are also ones that will continue to help my students far beyond the time with me and far beyond their time in school. There is so much that has been wrapped up in this unit that it is hard to capture all of it in words.

And as for which books will be our winners, we will just have to wait and see.