The Struggle For Both

For years, as a fifth grade teacher, I felt like I had to choose between helping kids develop a pure love of reading or helping kids develop skills of metacognition during our independent reading time. I knew that the research showed that when kids notice their own thinking, when they are metacognitive, then they were growing as readers. I also knew that there was nothing that provoked more whining and complaining from my fifth graders than being asked to stop and write as they read or to do longer pieces of writing about the reading that they were doing. So there were years I stopped the metacognition piece completely and just let kids read without asking them to notice or track their thinking in any ways. And then I would feel guilty. So the next year, I would swing the other way and double down and ask for kids to write down a certain number of thoughts as they read or fill our year with book clubs where there were strict guidelines of what they had to bring to each book club meeting in terms of the thinking they were writing down. And neither solution felt right. Neither solution felt like the whole of what I really wanted.

One of the things that I believe most strongly is that our job as teachers of reading is to help students develop a love of reading. And to do this, I truly believe that we need to let kids read the things that THEY want to read instead of limiting them to reading the things that WE think are “good” enough. That means that if kids want to read graphic novels, I want them to read graphic novels. If kids want to read Diary of a Wimpy Kid, then I want them to read Diary of a Wimpy Kid. If kids want to read every Harry Potter book for a fourth time, then I want them to read every Harry Potter book for a fourth time. This reading choice is imperative in helping them form the kind of reading identity that will be sustained outside of the classroom. Letting them figure out who they are as readers without me dictating what they should read is the only way that they will be able to exist as readers without me dictating that they should read. So whatever work I would ask my students to do as readers needed to allow for that kind of choice. And the problem was that too often, the work I was asking them to do was only possible in the “right” kinds of books. But I knew there had to be a way that I could do both. That I could allow them to read the books that they loved while also guiding them to do the kind of work that I knew (and research showed) would help them grow as readers. I just couldn’t figure out what that work might look like.

And then I had the absolute pleasure and privilege of becoming a Heinemann Fellow and we were asked to take on action research. And my action research centered around this very idea of how to help students become the metacognitive readers I wanted them to be while not killing their love of reading in the process. And in the years since then, I have continued to wrestle with this idea and work on a process that has finally allowed me to feel good about the work my students and I are doing in our quest to grow our love of reading and our skills as readers all at the same time. So I thought I would take some time to try and describe the work that we do as it currently stands.

It Comes Down to Inquiry (as it so often does)

When my students are really resistant to something I am asking them to do in the classroom, if I stop and reflect on why, it is almost always because they are too far from the center of the work. What I am asking them to do is not meaningful to them, it does not feel driven by their own thoughts and curiosity. In short, I usually need to find a way to weave more inquiry into the work. In my mind, inquiry is the closest that I have ever come, in my classroom, to mimicking the natural desire to learn that so freely exists in my students when they are outside of the classroom. It places them at the center of their learning and the motivation to learn does not need to be faked because they really want to know and understand something about the world.

So, when it came time to make a better process for our reading work, I knew that I needed to find a way to bring in more inquiry. How could I move my students closer to the center of the work that I was asking them to do?

It seemed the easy answer was to begin the entire process by asking them what they were already thinking about. And then build the work that I asked them to do from there. Too often, the work that I was asking my students to do during independent reading was based on a standard or our current learning targets or what I thought they needed to be doing. But what if I approached the work from the other direction? From the direction that began with the student’s own thinking and then worked in our standards and learning targets and other comprehension strategies? And so that is where I now begin. And it all starts with our reading conferences.

A New Purpose For Reading Conferences

For many years, I used reading conferences as a way to check-in with my readers and as a way to “hold them accountable” for the reading that I was asking them do. Sometimes, we would problem solve together, but, if I am being honest, a lot of times my conferences were simply a way to make sure they were reading, to make sure they were thinking about their reading, to make sure they were understanding their reading. And while these are all noble intentions, I grew to loathe reading conferences and do whatever I could think of to avoid them. They felt as meaningless and purposeless to me as they felt to my students.

But then I switched my thinking about these reading conference. Instead of trying to hold my students accountable (whatever that really meant), I began to use my reading conferences as an opportunity to help students realize the brilliant thinking they were already doing and then use that thinking in order to create a reading goal of what they were going to pay attention to as they continued to read.

The idea for these reading goals came to me as I was reading a book for a book club that I was a part of. I noticed that the main character in the book that I was reading would describe her emotions for other characters in one way and then she would act in a way that revealed that she really felt very differently about that character. So I decided that I would start marking all the places in the text where I saw this happen. As I did that, I began to better understand this character and developed a theory about why this was happening. When I came to my book club meeting, I was so excited to talk about my thinking with the rest of the group and because I had marked the text, I had plenty of places to point to as I talked about my theory. This made the reading exciting and it gave me real purpose in tracking my thinking and looking for text evidence. THIS was what I wanted for my students.

So I developed a way of doing a reading conference that would allow me to help students notice the thinking that THEY were excited about and then set a goal to help them continue to pay attention to that thinking as they read through the text and also help them to create a way to keep track of that thinking using a concrete system that would stay with them when I walked away.

If anyone is interested THIS IS THE FORM that I now use when I am doing a reading conference with my students. It changes every year, several times a year, based on what I realize my students need from me and what I need to make sure to provide to them. But this is the form in it’s current state.

When I sit down with a student, the first thing I always ask them is, “What have you noticed as you are reading?” I have found this question to be better than asking them what they are thinking and better than asking them to begin with a summary. For me, this question helps me get to the heart of what they are already doing and thinking about as quickly as possible. And of course, sometimes they respond with, “Nothing.” In that case, I make my questions a bit more specific, “What have you noticed about your characters?” or “What have you noticed about what the writer is doing?” And if it still does not get a response, I follow up with, “Okay, I am going to leave you to read for a little bit longer and I am going to just ask you to pay attention to what you are noticing and then I will be back to check in again. How long do you think you might need to do that?” And then I check back in. Most often, this is enough to get a conversation going.

One other thing that is great about this question is that it can be asked no matter WHAT THE KID IS READING. When kids are reading graphic novels, they are noticing things. When kids are reading Captain Underpants, they are noticing things. When kids are reading books written in verse, they are noticing things. The noticing is not limited to the right kind of books and so there is no pressure to try to force kids to read something that I determine to be the right kind of book. Instead, I am asking them to read what they love and to pay attention to what they notice within those books that they love.

As students share what they have noticed, my job is to really listen and notice the different kinds of thinking that they are doing. Often, kids (and teachers) don’t realize that they are already doing much of the work that we want them to do. Our job is to help them notice that thinking and name it so that they will be more likely to do it again. So as the students talk, I am writing down the different types of thinking that they are already doing so that we can use those thoughts to set a reading goal.

Here are what a few completed conference forms look like:

Using The Students’ Own Thinking To Create A Goal For Future Reading

Once the student has talked through what they are noticing, I then share with them some of the things that I heard them say. So if they noticed that the mom in the book seems to be making really bad choices and that the daughter is getting really upset, I might say to them, “So I notice that you are thinking about the relationship between your characters and noticing how one character’s choices are affecting another character.” Or if they noticed that the main character keeps getting into trouble but that trouble isn’t stopping the character from being bad, I might say, “So I notice that you are thinking about how a character’s actions are impacting that character.” I am taking the thinking they are already doing and I am pushing it forward just a little bit.

After sharing a few of the thoughts that I noticed, I then ask the student if any of those thoughts might work to create a reading goal of what they might pay attention to next. At the start of the year, most kids have no idea how to take what they noticed and use it to craft a reading goal. So at the start of the year, I often share a few possible ideas for reading goals (all based in thinking they are already doing) and ask the students which goal might work best for them. This is a process that many students internalize as the year goes on and take more responsibility for by the end of the school year.

So, for example, I might say to the student who was noticing the mom’s bad choices, “Maybe you want to pay attention to the choices that the mom makes, how those choices impact her daughter and why you think she made the choice that she did.” For the student who was noticing the boy who got into trouble, I might say, “Maybe you want to pay attention to the actions of the boy, the effect these actions had, and how you think these effects changed the boy and his behaviors.” I often give the kids two or three options for possible goals and ask them which goal they think would work best.

A System To Gather Text Evidence

Once students have chosen a reading goal that they think will work for them, we think about how they might create a system that will allow them to gather text evidence in connection with this goal. I don’t call it text evidence, I simply ask them to think about how they will keep track of what they are noticing. Usually, this involves some form of a chart that will provide space for them to keep track of what they notice in the text AND what they notice in their own thinking. Some kids choose to create this chart in their reading notebooks and other kids choose to use a Google Document. Whichever feels easier for them and less intrusive to their reading is where they end up collecting their text evidence.

The beauty of giving the kids a tool like this before I walk away is that it provides a clear and concrete structure for the kids on how they can continue to pay attention to one line of thinking throughout an entire text. Too often, we ask kids to do some really abstract thinking that they do not fully understand and then we are surprised when they don’t continue that thinking after we walk away. By giving the kids a chart to use that is designed around what THEY want to pay attention to, we are leaving a scaffold behind after we have moved on to the next student. And, if we craft it correctly, that scaffold can push the students towards deeper thinking while remaining connected to the thinking that a student is already doing and is already interested in.

As I work with the student to craft a way to keep track of what they notice as they continue to read, I also make sure to work in my teaching point. This is when I think about all of the learning targets and standards that I want my students to understand by the end of their fifth grade year and I think about how I can weave just one of those standards or skills into the reading goal that we have just set. This sounds harder to do than it really is. Because the truth is, once you know the standards and know your learning targets well, it is fairly easy to blend them into the work that our students are already doing. By thinking of the skills and standards simply as things that good readers do, it is easier to work them into a teaching point connected with these reading goals. For example, one of the things my fifth graders work on is synthesis. Putting together pieces of information in order to grow their understanding. So, if I am setting a reading goal with a student to notice the choices that the mom in the book makes and how it affects her child, I might say something like, “As you learn more about this character and about her choices, you will be able to put that information together in order to better understand this one character and the relationship between her and her child.” Then I might model an example. And there is the teaching. Often times, I can work this teaching point right into the chart that my students and I create.

Here are what some of those charts look like:

Depending on my reader, we might fill in an example together so that I can leave behind one example for them to look back on. Other students do not need this as much. But either way, when I walk away, I know that I am leaving behind a structure for my students to use in order to continue to think about one line of inquiry throughout the rest of their text and also a structure that will continue to push them to think deeply about text evidence while I move on to work with other students.

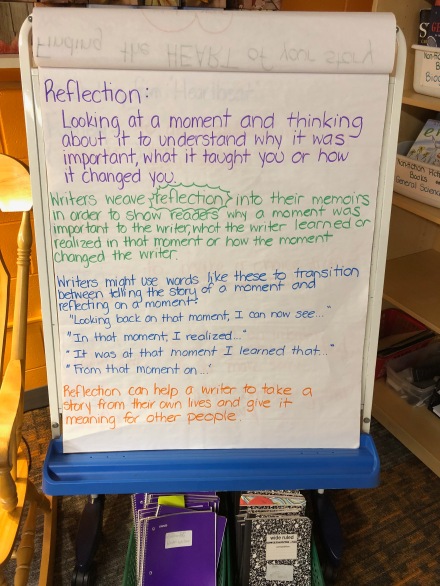

Reflecting Back on Our Thinking: Writing About Reading

I don’t believe that any of this would really work, if I did not ask my students to use the notes that they took as they were reading. Part of what motivates my students to continue to add to their thinking after I walk away is that they know they will need to use those notes for some greater purpose. And I am VERY honest with my students about the purpose for writing about their reading.

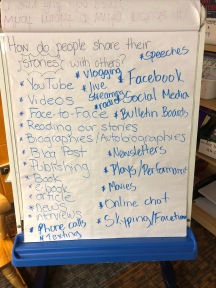

In our classroom, the vast majority of the writing that we do is for an authentic purpose and an authentic audience. We write memoirs in order to show others who we are and to teach them lessons we have learned from our own experiences, we write pieces of persuasive writing to those who have the power to make the changes we want to see in the world and we write informational texts in order to reveal previously hidden or left out information that can help others to see the world more accurately. And for years, I tried to lie to my students that they were writing about their reading for an authentic audience that existed beyond the classroom. Now, yes, people write about what they are reading for authentic purposes outside of the classroom. I know that people write book reviews and write about books they are reading in book clubs, but that isn’t REALLY the kind of writing about reading that I wanted my students to do.

But, again, I also knew that writing about their reading would help them. I knew it would help them to do literary analysis further along in school. I knew it would help them to push their thinking about their reading as they were forced to wrestle with ideas in writing. I knew it would help them to learn how to support their claims with text support. I knew that it would help them to learn how to write about reading in a way that they will be asked to do on standardized assessments that are an unfortunate reality in our world. And, most importantly, I knew that it would help me to more accurately assess what my students were learning how to do as readers and it would give me the concrete evidence that I needed in order to share with others what each student was able to do.

So that is when I realized that I did not need to make up some greater purpose for the writing about reading that I was asking my students to do. Instead, I needed to be honest with them. I needed to be transparent. And so now, I am clear from the very beginning that every three-four weeks, I will ask my students to complete a piece of writing about their reading and their reading goals. They will be asked to write about one reading goal and the thinking they have done in connection with that goal. When they write, they might be in the middle of the book they will write about or it might be a book that they have already finished. But I am very clear on why they are writing. This is NOT writing that is for an authentic audience that exists beyond our classroom. This is writing that is being done in order to push their own thinking as readers by asking them to look back on the notes that they have taken while reading and reflect on what those notes have helped them to better understand. AND this is writing that is for me. This is their assessment. Their writing provides me with evidence of what they have learned how to do as readers and that is evidence that I need in order to know what they have learned, where they are ready to go and how to share that information through report cards and with their families and other teachers. It seems that when my students are able to clearly understand why they are doing this kind of writing, then they are much more willing to do it without complaining.

So after my students have their reading goals up and running, I then share with them an example of my own writing, using the notes that I have taken as I read. Every year, I make sure to write a new piece of writing about my own reading so that they can see that this is work I am doing as well. This year, I was reading the beautiful book, My Jasper June while I took notes connected to my own reading goal and then used those notes to write about my goal and what it helped me to understand. Here are what my notes looked like:

I then shared with my students how I took those notes and wrote about them in a way that pushed my thinking. If you are interested, HERE IS THE WRITING ABOUT READING THAT I DID AND SHARED WITH MY STUDENTS.

After reading this piece of writing together, as a class, we think about what was included in this piece of writing. I chart our ideas and then create a checklist that shares the major parts of a reading blog post. Each year, the checklist looks fairly similar.

After that, I introduce the rubric that I use in order to assess their pieces of writing. Each year, I have one rubric that I use for the first part of the year with my fifth graders and then midway through the year, I increase the expectations and create a second version of the rubric to use for the second part of the year. This is because I always see such tremendous growth in my students’ writing that before too long, many students are exceeding the first set of expectations.

Here are the two rubrics (and checklists) that I use with my fifth graders:

RUBRIC FOR WRITING ABOUT READING AT THE START OF THE YEAR (Student Samples Included)

RUBRIC FOR WRITING ABOUT READING AT THE END OF THE YEAR (Student Samples Included)

Each year, I make adjustments to the wording of this rubric. What I love about creating my own rubric, as opposed to using an assessment tool created to go along with a program or purchased set of resources, is that I can make whatever adjustments feel necessary in order for the rubric to really be a tool that guides my students’ thinking and learning. I am not held back by the specific lessons that are included in a purchased program or the language that is attached to whoever is making money off of me using their rubric. Instead, I can really think about what I want my students to be able to do and adjust the language on the rubric to help guide them there.

Included at each level of the rubric is a link to a student-written example of writing about reading at that level. I know that kids are often overwhelmed when I share my own writing about reading, so I have found that it is helpful for the kids to be able to see what a student-written example looks like at each level of the rubric. I am surprised, year after year, how often the kids open these examples and use them as mentor texts while they craft their own writing about reading.

As I said, I ask the students to complete a piece of writing about reading every three-four weeks. This provides them enough time to develop their thinking across a text between their pieces of writing. Some students will finish two or three books in this time and will write about the goal that led them to the most thinking. Other kids, will be in the same book across two assigned pieces of writing about reading. Those students will write about the same book two different times and will even sometimes still have the same reading goal. What will change, however, are the examples that they share and the reflection that they are able to do when they look back at those examples and write about what they were able to better understand.

When the student submit their writing, I highlight the level on the rubric that I believe matches the evidence the students have provided of their thinking about their books and goals in their piece of writing. I also leave written comments on every piece of writing explaining what I notice they were doing and how they might go even farther for their next piece of writing. Once I have returned their pieces of writing, I start the three week or four week count again for when the next piece of writing is due.

I also make sure to pull two or three student examples to share with the rest of the class each time a piece of writing about reading is due. I ask these students for permission to use their writing to teach the rest of the class about what I hope to see from their work. In the days after their writing about reading is returned, I use these student-written mentor texts to teach targeted mini-lessons in the kinds of thinking, reading and writing that I am hoping that all students will start to do. This is one of the most motivating pieces of instruction throughout the entire year. When kids can see what their classmates are doing, they can better envision themselves doing it as well and I often notice a change in the next round of submitted writing.

This process, of noticing our thinking, setting reading goals, gathering evidence to show progress towards these goals and then looking back and reflecting through writing on what these goals helped us to better understand, sustains us throughout the entire year. It gives me an incredible amount of meaningful data of what my students are able to do as readers (and as writers). It provides me with a beautiful view of the growth that my students make as readers throughout the year. And, most importantly, it has made our writing about reading feel so much more meaningful and so much more centered around the students themselves.

I cannot imagine that anyone is still reading this behemoth of a blog post, but I am happy to have all of this written down in one place. If there is anything that ties together the work that we do during independent reading in my classroom, it is this process. This process has allowed me to truly find a way to honor all of the choices that I want my students to make as readers while they are in my classroom while also honoring the work that I need them to do as readers while they are with me in order to ensure that they grow and develop new skills as readers and thinkers. It certainly is not a perfect process and each year this process grows and changes but it has created a space for me and for my students to develop our love of reading and our skills as reader all at the same time. And that is no small thing.