One of the phrases that people most like to share with me is, “You don’t know what you don’t know.” And yes, I suppose that is true. But I also think that it can become a convenient excuse for our own ignorance. If the, “You don’t know what you don’t know,” becomes an endpoint, then it allows us to continue to live our lives in willful ignorance, with a warped perception of our world based solely on our own limited experiences and knowledge. I wish instead that we would shift our focus and instead be as willing to say, “There is so much that I do not know and it is my responsibility to go and seek that information out.” I know that it is not quite as catchy, it’s a bit more of a mouthful, and it certainly requires much more work on our part, but I believe it is a shift that can start to repair some real damage in this world.

It is with this shift in mind, that I entered into our final literacy unit of the school year this past May with my fifth graders. The first part of our unit focused on helping students to confront their own biases. That work can be read about in THIS POST from two years ago. One of the most important parts of this first work is helping students to see that when we are subjected to narrow sets of information about entire groups of people that are repeated to us over and over again, they can form stereotyped ideas that we carry around with us about those groups of people. These are what start to form our biases and these biases lead us to inaccurate and harmful beliefs. Once students saw how limited information can lead to misunderstandings about people, we then shifted our focus to look at how our biases can lead us to misunderstandings about texts as well, specifically when we are looking at texts about history.

There are several reasons that we focus specifically on history. One is a matter of covering curriculum (never a great reason to do things, but a necessary one). For fifth grade, the Civil Rights Movement is a part of our social studies curriculum. Because of time and the never-ending and often-lost battle of attempting to get it all in, we have always covered the Civil Rights Movement through our literacy curriculum. And beyond that, I think that when we read about history, we need a specific set of skills as readers. Too often, our students read about history only to absorb the specific content, without learning a process through which they can walk on their own in order to learn about moments in time in a responsible way. By focusing on teaching how to read about history, specifically, we are able to ensure that our students are learning how to read in a way that gives them a more accurate understanding of history.

And lastly, so much of what our children are given when they are young (and also when they are older) in order to learn about history is just wrong. Things are missing, truths are ignored, voices are silenced. But, like people always say, “You don’t know what you don’t know.” And if we stop there, if we allow that to be the phrase that guides us, then we will continue to deny the truths in our history that could actually help us to better understand our world today in a way that could lead to real change. And we will become complicit in allowing our students to grow up with misunderstandings about our world and our history.

So we tackle how to read history and we look at it through the lens of how to uncover hidden and neglected information in order to help us overcome our biases and misconceptions about history.

Part of what I am always trying to do with my students is to find a concrete way for them to really see the kinds of problems that I want to help them to overcome through reading and writing in a different way. It would be easy for me to tell my kids that they have misconceptions about history because of the way they have been reading and learning, but it is much more powerful if I can find a way to really show them those misconceptions.

So, this year, I wanted to do that using a single figure who I believe all of my students carry extremely limited understanding of and strong misconceptions about: Martin Luther King, Jr. For many of my fifth grade students, when they enter into our Civil Rights Movement study, the only knowledge they carry is around Martin Luther King, Jr. And much of that knowledge is wrong or extremely watered down. Again, I could tell them this, but I believe it is much more powerful if I am able to show them. And since our unit on reading about history centers on the Civil Rights Movement, this seemed like a perfect entry point.

After reminding the kids what we learned about how biased messages form in our brains about groups of people when we are giving the same set of narrow and limited information over and over again, I told the kids that the same thing can happen about moments in time in our history.

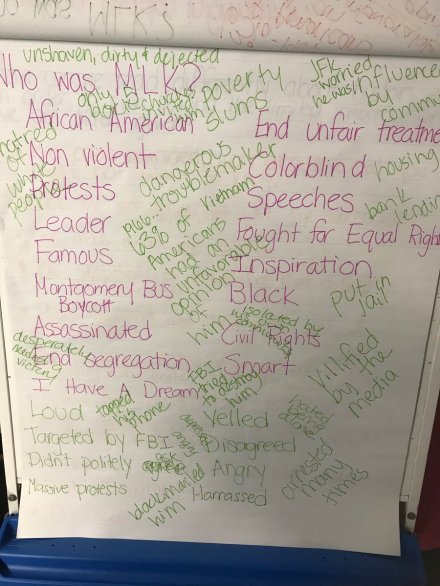

I then shared with the kids a VERY simplified, and also very typical, biography about Martin Luther King, Jr. to read. You can find the text that we used HERE. After reading the text together, I asked the kids to answer the following question in writing, “After reading this brief biography and knowing everything you already know about Martin Luther King Jr., think about what you understand about who he is. What is your CURRENT understanding of who Martin Luther King Jr. was? What do you know about him?” I gave the kids a few minutes to write and then asked students to read their answers out loud. As I listened to their answers, I started to chart the words and phrases that I heard come up in their answers over and over again. Our chart started to fill with words and phrases such as, “activist, peaceful, fought racism, African American, black, nonviolent, inspiration, disliked by some whites, hero, speeches, I Have a Dream, marches, etc.” The words and phrases reflected what I expected was the understanding that most of my students had about MLK. A watered down and overly simplistic understanding of the complex human that MLK was and a complete unawareness of the very complicated and upsetting relationship that our country’s government and many of our country’s citizens had with this man who is now seen as a hero.

So now that we had an idea of what we understood about MLK, I wanted to show them just how much they were missing. So I carefully curated a text set that included four short excerpts that showed parts of MLK’s life that were missing from my student’s current understanding. This is the text set that we used (It begins on page two of this document): A More Complete Understanding of Martin Luther King Jr.

Over the net two days, my students and I worked through these short, but complex, texts together. I read the texts out loud and I asked my students to underline or highlight any information that they found new or surprising. After each text, I asked them to stop and share what they had underlined. As we worked through the texts and shared the new understandings that we were gaining, I went back to the charts we had made with the lists of words and phrases that reflected our understanding of MLK. As our understanding grew, I used a different color marker to add NEW words and phrases that explained what we were coming to understand about MLK. Here are the two charts from my two classes that show the progression of our growing understandings.

After reading the additional texts, I again asked the kids to reflect in writing. I asked them the three questions that are on the last page of THIS TEXT SET DOCUMENT. We talked about how limited our understanding of MLK had been. We connected it back to this previous work that we had done in confronting our own biases about groups of people. When we were given the same, limited, information of what a “girl” is or what a “boy” is over and over again, that information shaped what we believed a girl and boy really were in a way that was far from accurate. In the same way, when we have been fed the same, limited, information about who Martin Luther King Jr. was over and over again, that information shaped who we believed Martin Luther King Jr was in a way that was far from accurate.

The kids quickly came to realize that they had been given an overly-simplified version of a very complex man. And, because kids are wise and desperate to know full truths, they quickly expressed anger that so much truth had been kept from them. We began to talk about how adults often doubt what children can handle, that they want to try to protect them from things that are messy and complicated and real. And as one of my brilliant students said this year, “Really, they say they are trying to protect us, but really they are just kind of lying to us.”

This then led us to a discussion about history and text books and the voices that are privileged and those who have traditionally been ignored. And we talked about why adults might leave the harder to understand stuff out of history and the stuff that makes our history and our country look less than good. We talked about the story we have been told about our treatment of Native Americans and how the story is often told in a way that leaves out the parts that show the truth about the awful ways our country treated this entire group of people. We talked about how when we are not given the whole truth about history, we cannot fully understand where we are today. And we all decided that we wanted to do better, as readers and as learners, in order to gain that more complete truth. As a class we talked about how it is our OWN responsibility to seek out the truth when we read about history and we cannot simply accept that what we are being given is enough.

So we then made a list. A list of the things that we thought we might be able to do in order to help us notice when something we are given feels incomplete and also a list of things that we can always make sure to do to help us better ensure that we are getting an accurate understanding about history. Here is what that list looked like:

So with this list in mind, we moved further into our study of the Civil Rights Movement and as we read, we continued to look back at this list to ensure that we were learning to read about history in a way that gave us a better shot at gaining a complete and accurate understanding.

And the beauty of this work is that the kids are so open to it. They are so very willing to admit that the way that they had been reading and learning up until now wasn’t working, it was flawed, it was problematic and they wanted to do better. And so as we learned the content we needed to learn, as we learned about this very important moment in American history, we were also learning something bigger. We were learning a process, a way of reading, that they could use in their lives outside of our classroom walls in order to better learn about their own history and the history of the world we live in. And that, is an incredibly powerful kind of learning to be lucky enough to be a part of.

It is this work that I believe will move us. I believe it will move us from being a world where we simply accept that, “You don’t know what you don’t know,” to a world where we are truly willing to say, “There is so much that I do not know and it is my responsibility to go and seek that information out.”

Excellent post. I agree with the statement “adults often doubt what children can handle,” but would also point out (which you do earlier in the post) that textbooks and curriculum typically leave out those deeper elements because they only have so much room (and time) to “cover” too much material.

I think those deeper discussions help students build context on topics that they often have very little of prior to encountering them in a classroom. No prior connection, no context. Because, after all, “you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Excellent post. I often struggle with what to teach our kids. I have been chastised for sharing some of the less than glowing information about MLK. I want my students to see him a human, with all the entrapments that go along with humanity, not as the mega – God that people like to remember him as. He did great things, no doubt,

but not without the human struggles that accompany doing great things. I think it’s important to know the truth. Again, a terrific post. Thank you.